Neanderthal Extinction

- Wu, Bozhi

- Mar 19, 2021

- 4 min read

Neanderthal was a particularly interesting hominin species, not only because it was one of the closest relatives of modern humans, but also because of its unique anatomical and cultural features, including but not limited to the Mousterian stone-tool industry, the possibility of complex and symbolic behaviors, and their potential interbreeding with H. sapiens. As a result, the extinction of Neanderthals and its potential reasons have become key questions for paleoanthropologists, and a variety of causes and explanations have been proposed.

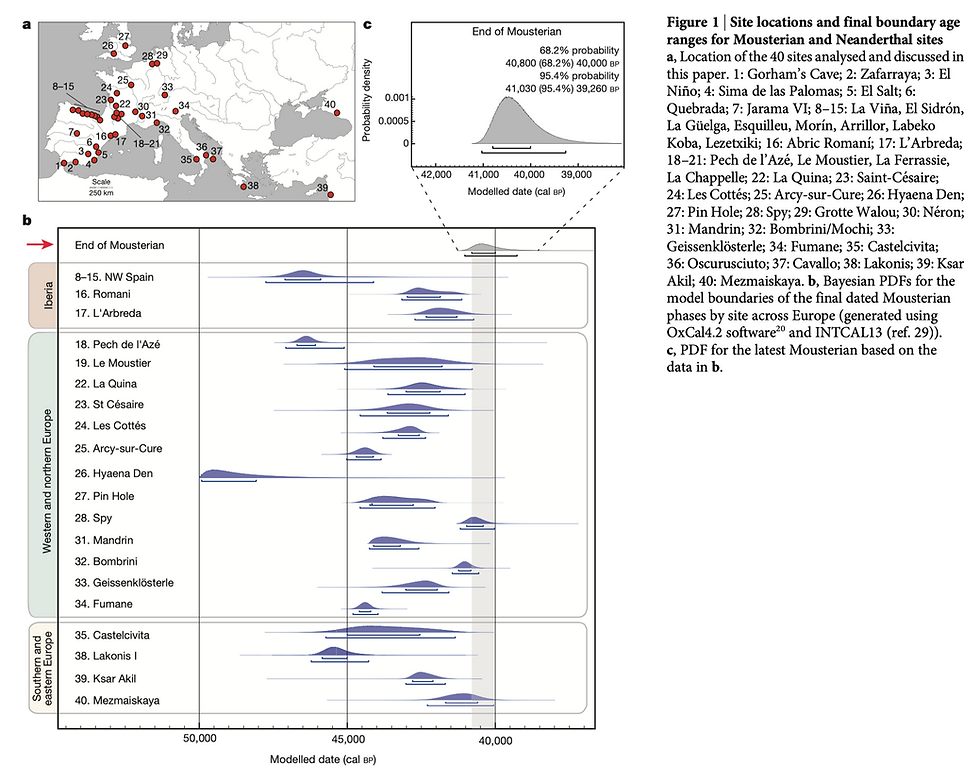

In a study of the spatiotemporal patterning of Neanderthal disappearance, Higham et al. (2014) estimated that Neanderthals went extinct in Europe around 40,000 years ago. Interestingly, it was approximately around the same time when the earliest anatomically modern humans (AMHs) migrated out of Africa and entered Eurasia. And it was shown that there could be a significant temporal overlap between Neanderthals and AMHs. Furthermore, genetic studies have also reviewed an introgression of 1.5-2.1% of Neanderthal-derived DNA in all modern non-African human populations, suggesting interbreeding of these two populations outside of Africa (Green et al. 2010).

Some of the major proposed causes of extinction include climate and environmental changes, transmission of diseases, and competition with AMHs. Therefore, I would like to briefly discuss each of them in the following essay.

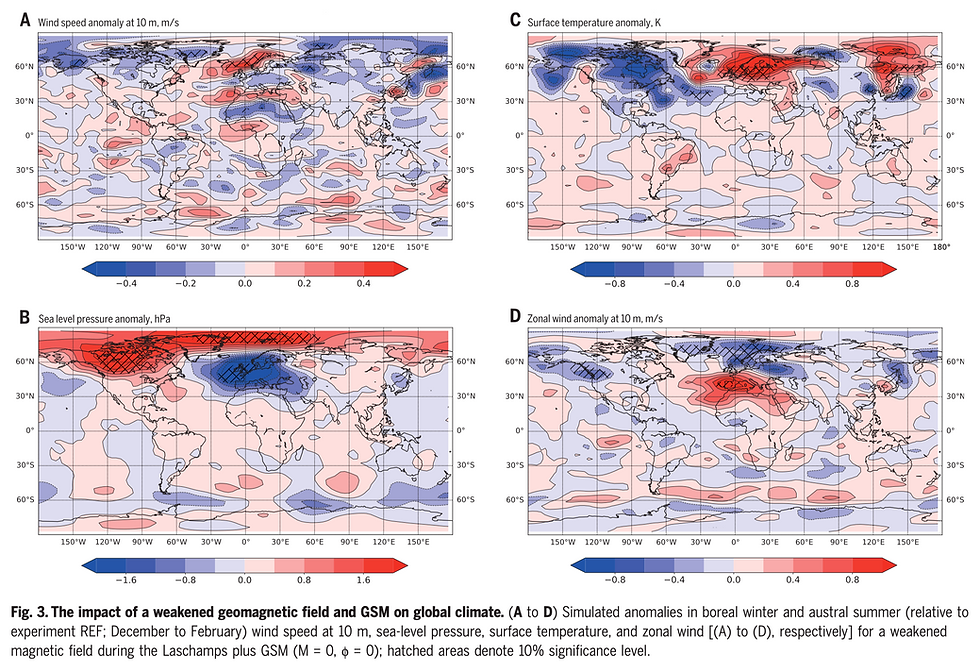

Climate change has often been proposed to be a part of the explanation for certain evolutionary events, as evolution was essentially about how species adapt to the environment. For example, Neanderthals might have failed to adapt for a rapid glaciation, or fluctuations in climate might have resulted in a loss of habitat or prey for Neanderthals, leading to their eventual disappearance. A recent study has suggested the potential role of the last major magnetic inversion called the Laschamps Excursion in leading to a global environmental crisis that took place at around 42,000 years ago (Cooper et al. 2021). Contrary to the previous beliefs, they have indicated how factors such as increased atmospheric ionization and decreased stratospheric ozone levels could have generated significant climate impacts, impacting the Neanderthal population. However, according to Tzedakis et al. (2007), the relative role of climate change in Neanderthal extinction may be highly dependent on the exact timing of their disappearance, as different dates were connected with dissimilar climate contexts. Therefore, more accurate dating of the extinction event in the future might have important implications for our interpretation.

Another hypothesis involves the potential transmission of diseases between Neanderthals and AMHs. In a computational modeling study, Greenbaum et al. (2019) have suggested this possibility as Neanderthals and AMHs had likely acquired immunity and tolerance to distinct sets of pathogens throughout their independent evolutionary process. As a result, when the two groups first encountered each other, this inter-species transmission might be critical and might have created burdens for both groups. Interestingly, there could be asymmetry in terms of their ability to recover from the attack, and this could be critical for the later replacement process.

And more intuitively, the spread of AMHs into Eurasia might have led to either direct or indirect competition between the two groups. For example, some have suggested the possibility that AMHs might be more effective in exploiting scarce resources than Neanderthals in relatively similar niches (Timmermann 2020). And theoretically, this could happen in the absence of contact, and, therefore, does not necessarily involve violence or war between the two populations (Banks et al. 2008).

I think factors like competitive exclusion, abrupt climate change, and transmission of diseases could have all played a role in the extinction of Neanderthals. It is relatively unlikely for one of these factors to be the mere cause of such a large-scale extinction event across multiple regions and time. Personally, I consider disease transmission might have played a relatively more important role, reminding me of what Dr. Jared Diamond has pointed out in his work Guns, Germs, and Steel. I think comparing to climate changes, the presence of AMHs and the introduction of new pathogens could have generated a more penetrating while widespread impact on the Neanderthal population. If so, the asymmetry of impact on the two populations becomes a central problem to be answered.

To conclude, for us to determine the relative role of these factors, more investigations on the environmental changes, Neanderthal-AMH interactions, and the spatiotemporal pattern of Neanderthal disappearance were necessary.

References

Banks, William E., Francesco d’Errico, A. Townsend Peterson, Masa Kageyama, Adriana Sima, and Maria-Fernanda Sánchez-Goñi. 2008. “Neanderthal Extinction by Competitive Exclusion.” PLOS ONE 3 (12): e3972. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0003972.

Cooper, Alan, Chris S. M. Turney, Jonathan Palmer, Alan Hogg, Matt McGlone, Janet Wilmshurst, Andrew M. Lorrey, et al. 2021. “A Global Environmental Crisis 42,000 Years Ago.” Science 371 (6531): 811–18. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb8677.

Green, Richard E., Johannes Krause, Adrian W. Briggs, Tomislav Maricic, Udo Stenzel, Martin Kircher, Nick Patterson, et al. 2010. “A Draft Sequence of the Neandertal Genome.” Science 328 (5979): 710–22. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1188021.

Greenbaum, Gili, Wayne M. Getz, Noah A. Rosenberg, Marcus W. Feldman, Erella Hovers, and Oren Kolodny. 2019. “Disease Transmission and Introgression Can Explain the Long-Lasting Contact Zone of Modern Humans and Neanderthals.” Nature Communications 10 (1): 5003. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12862-7.

Higham, Tom, Katerina Douka, Rachel Wood, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Fiona Brock, Laura Basell, Marta Camps, et al. 2014. “The Timing and Spatiotemporal Patterning of Neanderthal Disappearance.” Nature 512 (7514): 306–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13621.

Timmermann, Axel. 2020. “Quantifying the Potential Causes of Neanderthal Extinction: Abrupt Climate Change versus Competition and Interbreeding.” Quaternary Science Reviews 238 (June): 106331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106331.

Tzedakis, P. C., K. A. Hughen, I. Cacho, and K. Harvati. 2007. “Placing Late Neanderthals in a Climatic Context.” Nature 449 (7159): 206–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06117.

Comments