Defining the Genus Homo

- Wu, Bozhi

- Mar 19, 2021

- 3 min read

As mentioned in Collard & Wood’s article (2015), the theoretical and practical definition of “genus” as a taxonomic category is crucial for our understanding of the evolution of genus Homo. Without a well-defined guideline upon which scientists could rely on to classify the newly discovered fossils, the criteria and interpretation of the genus Homo will likely be updated with each new discovery of Homo-like species and their morphological characteristics. Here, I would like to briefly review three relatively feasible while distinct definitions for the genus concept.

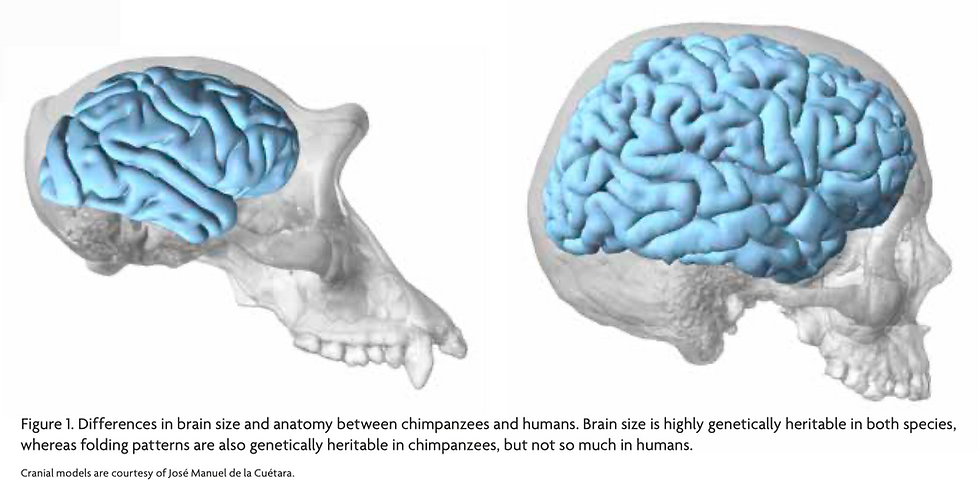

The first definition was originally proposed by Ernst Mayer, and the main focus is on the ecological niche or adaptive plateau of the species. In addition to the shared common ancestry, members of a genus are required by this definition to differ in a significant manner from species in other groups in terms of their adaptive plateau and morphological characteristics. For example, while Australopithecus typically still exhibit adaptations for tree dwelling and have relatively small brains and bodies, the genus Homo may show more traits related to obligate bipedalism, tool-making, and have overall larger endocranial volumes, more gracile cranium, mandible, and postcranial elements, etc. However, his definition also allows for the existence of paraphyletic genera, which differs from the next definition I am going to introduce.

The second definition by Wood & Collard is built upon Ernst Mayer’s definition and states that species that belong to a monophylum and occupy a single adaptive zone should be defined as a genus. It differs from Mayer’s definition as it allows species in different genera to occupy the same adaptive zone, instead of requiring every genus to occupy a distinct and unique niche. And as aforementioned, it also excludes paraphyletic taxa.

Another similar definition was argued by Cela-Conde and Altaba, but it also differs from Wood & Collard’s definition in one significant way. They have raised the concept of species germinalis, which could be interpreted as the ancestral species that have given rise to the other species in the genus. Unlike the other two definitions, this definition allows species from the same genus to occupy two, instead of one, adaptive plateaus, with one being more ancestral and the other being more derived.

Overall, the three definitions’ main divergence centers on whether paraphylum genus should be accepted, how we should incorporate the species’ adaptive characteristics into the designation of their genus, and whether a single genus can occupy multiple adaptive zones. Although there does not exist an absolute and explicit criterion for us to evaluate these different approaches, I agree with Wood & Collard’s argument that their definition of the genus is relatively more explicit and easier in practice. Their definition has rendered equal importance to the phylogenetic relationship and the adaptive characteristics when assigning fossil species into the Homo genus, as they require both closer phylogenetic relatedness and more similar key adaptive variables to H. sapiens, the type species of the genus. Furthermore, its monophyletic standard could also provide researchers with a stricter criterion on the new species’ phylogenetic relationship when grouping them into genus. In Cela-Conde and Altaba’s definition, the determination of the species germinalis of a genus is essentially a hard problem by itself. And no explicit criterion for identifying the “decided morphological gap” has been offered by Ernst Mayer also, which might be less helpful for guiding future discoveries.

Viewing the genus Homo from Wood & Collard’s perspective, both H. habilis and H. rudolfensis are more similar to Au. africanus – the type species of Australopithecus – than to H. sapiens in terms of their key adaptive traits. The evidence includes but is not limited to their more ape-like life history strategies and more primitive limb proportions, which are indicative of their facultative bipedalism. As a result, the authors have proposed the modification of moving H. habilis and H. rudolfensis into the genus Australopithecus and largely retaining the other genus classifications.

References

Collard M., Wood B. (2015) Defining the Genus Homo. Handbook of Paleoanthropology, 2107-2144. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-39979-4_51

Comments