Reason and Emotion: The Evolution of Two Interacting Systems of Morality

- Wu, Bozhi

- Jun 7, 2019

- 12 min read

Updated: Mar 19, 2021

Introduction

Humans are special. While we have shared 4 billion years of evolution with all the living species around us, we are the only species who has developed full language, built up cultures and countries, created advanced technologies, artworks, and so on. In parallel with these unique achievements, we have also developed concepts of morality, which might act as the foundation for our evolved ability to sustain extremely large-scale cooperation without leading to eventual chaos. Every day, we are constantly and automatically evaluating the events and behaviors happening around us, judging whether they are good or bad, right or wrong. Nevertheless, morality has also posed numerous great puzzles for us, as there does not seem to be an explicit, overarching rule that can accurately predict human moral judgments under all kinds of conditions. While people generally hold some forms of rules or axioms that they typically follow, they also encounter moral dilemmas where they feel extremely difficult to make the “right” choice and eventually violate their rules. Therefore, several questions need to be answered. How exactly are moral judgments being made? What kinds of mental faculties are employed? What causes people’s inner conflicts when they confront moral dilemmas? And finally, what will be the adaptationist explanation for the evolution of this complicated system of morality?

In this paper, I will first provide a brief review of the distinctive roles philosophy and science should play when approaching the study of human morality. Then, through the discussion of multiple empirical studies, several influencing factors of our moral judgments and therefore the complexity of our moral system will be illustrated. Finally, taking an evolutionary stance, viewing morality as a psychological mechanism evolved to increase our cooperativeness and therefore fitness living within social groups, I would like to introduce my theory which views moral judgments to be the results of the interaction between two systems of morality – Moral System Based on Emotion (MSE) and Moral System Based on Reason (MSR). And I would also like to offer an “evolutionario” (evolutionary scenario) that could potentially explain how these two interacting subsystems develop in the history and eventually result in the complex system of morality possessed by modern human beings.

Our Confusing System of Morality

Philosophy vs. Science and Reason vs. Emotion

In the history, great philosophers like Locke (1975), Kant (1998), and Mill (1998) basically contend that moral judgments should be made based on reason or rational thinking, overriding passions. In their ethical theories, they derive prescriptive rules such as “the principle of utility” (Mill, 1998) and “the categorical imperative” (Kant, 1998) that they think people should follow to make the “ideal” moral judgments. On the contrary, Hume views emotion to be a critical and necessary ingredient in the formation of ethical judgments and famously stated that “[r]eason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions” (Hume, 1738, p. 415). However, as the job of modern science is to take a descriptive rather than prescriptive approach towards a better understanding of how human morality works, whether we “ought to” follow our reason or emotion or which one is more desirable is beyond the scope of scientific discussion, and we should instead focus on how moral judgments are naturally being made. Based on research in psychology and neuroscience, we are now confident enough to conclude that emotion and reason are both playing central roles. Nevertheless, we have also found that various kinds of factors can influence their relative contributions to the decision-making process. In the following section, I would like to briefly discuss several empirical studies that have suggested the impact of these factors and demonstrate the complexity involved in our moral system.

Factors Influencing Moral Judgments

Actor vs. Observer

If morality is essentially rational, then the evaluation of the moral character of a behavior should be completely independent of people’s perspectives. However, according to Nadelhoffer and Feltz’s study (2008), framing effect and actor-observer bias are found to be operating in morally-related conditions as well. In the experiment they have conducted, they revealed that participants actually consider the same moral violations to be more permissible when they viewed them from the third person perspective (3PP) comparing to the first person perspective (1PP), probably due to the higher emotional arousal involved in the latter scenario. In general, differences in people’s moral judgments between 1PP and 3PP conditions have been consistently reported by researchers, and, based on an ALE meta-analysis of 31 studies, distinct neural correlates and therefore mental faculties have been observed to underlie the differential appraisals of moral events with changes in perspective (Boccia et al., 2017).

Personal (Direct) vs. Impersonal (Indirect)

Joshua Greene is one of the pioneering scientists who applied modern neuroscience technologies into investigating the neural activities involved in moral judgments. In one of his classical fMRI studies, he adopted the classical thought experiments in ethics – trolley dilemma (the impersonal/indirect scenario) and its variation footbridge dilemma (the personal/direct scenario) – into empirical investigation (Greene, 2001). What he has found was significantly higher activation of the brain regions associated with emotions when the participants were evaluating the more personal scenario, which involves direct physical contact with the victim. This result is in line with people’s general reluctance to directly push a stranger off the footbridge to save five people, conflicting with “the principle of utility.”

Intentional vs. Accidental

Another crucial factor, also implied in Kantian deontological ethics, is the intentionality of the actor involved in the moral event. While intuitive, this postulate has been supported by numerous studies, revealing that the affective evaluation of moral violations, even when leading to identical physical consequences, are categorically different in the intentional conditions and the accidental conditions (Baird & Astington, 2004; Gan et al., 2016; Greene et al., 2009; Nobes, Panagiotaki, & Bartholomew, 2016). From the neuroscience perspective, in intentional conditions, brain regions including left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate gyrus, and left amygdala are found to be activating at higher levels, and participants’ ratings for the inappropriateness of the behaviors are also observed to be significantly greater (Berthoz, Grèzes, Armony, Passingham, & Dolan, 2006)

Audience vs. No Audience

As our sense of morality is likely evolved to enhance cooperation among individuals living in the same social group, whether a moral event or behavior has been observed by others or not is hypothesized to be another critical influencing factor. In one study, the effect of witnesses on the neural responses to moral events is examined by using fMRI, and increased left amygdala activity was discovered to be associated with the presence of audience in all conditions (Finger, Marsh, Kamel, Mitchell, & Blair, 2006). Furthermore, according to the participants’ self-report, feelings of shame and embarrassment are significantly stronger in scenarios with the witness of an audience. This result is predicted from an evolutionary perspective, which views these two emotions as products of the evolutionary pressure favoring the development of psychological mechanisms to detect responses of other individuals in the social group and avoid behaviors that are antisocial and potentially harming one’s own fitness.

Based on these empirical studies, it is clear that a wide range of factors is constantly affecting the relative contributions of reason and emotion during the human moral judgment process. Instead of following a straightforward, explicit rule, humans rely on the integrative processing of multiple factors and correspondingly utilize multiple brain regions to compute for those different components. Lastly, it is crucial for us to realize the potential interplay between all of those influencing factors, which may become a prosperous field of research, based on the intriguing findings in some pioneering attempts (see Berthoz et al., 2006; Greene et al., 2009).

An Evolutionario of Morality Evolution

From what we have observed, emotion and reason are the two fundamental forces guiding human behaviors. And as our levels of emotional arousal are constantly influenced by various kinds of environmental factors, the moral conclusions made by these two different moral subsystems (MSE & MSR) are sometimes in conflict. So, what exactly has led to the evolution of this complex moral system involving two interacting subsystems of morality? Although we are not even close to having a thorough understanding towards its exact evolutionary pathway, in the following section, I would like to present one of the evolutionarios that could have potentially explain the formation and the functionality of these two interacting moral systems.

Moral System Based on Emotion (MSE)

Before the formation of culture and large-scale cooperation, the concept of morality did not exist, and certain emotions were evolved as internal rewards or punishments toward stimuli related to fitness changes. While animals that did not live in social groups simply had emotions to help them deal with environmental stimuli and respond in a way that increases their fitness, animals that did live in social groups have also co-opted emotions to become motivators for enhancing cooperation among individuals. (The detailed explanation for how and why cooperation or “altruism” could have evolved is beyond the scope of this essay. However, for the logic of evolution to make sense, it is necessary to understand that enhancing cooperation is essentially enhancing the fitness of the individual, at least before the presence of culture.) As a result, a primitive form of proto-morality has developed, as certain behaviors were either encouraged or discouraged based on their effects on the overall cooperation in the group. Emotions like sorrow, fear, anger, shame, guilt, etc. might have all contributed to either motivating or preventing certain kinds of behaviors, and certain levels of theory of mind (the ability to attribute the mental states of others) and empathy could also have played a role in this process. Eventually, this form of proto-morality developed and became the foundation of the current MSE we have. When the moral events involve kin, friends, or others who live closely within our group, when they are presented to us in a way that is in accord with the proper domain of our MSE, when the moral judgments we made are transparent to the other individuals around us, emotional arousals would be stronger and have larger influences on our decision-making process. From an evolutionary point of view, this is reasonable as, for instance, the death of my brother has a higher impact on my fitness (in terms of gene frequency) than the death of 5 strangers living in another community. This kind of moral standard is probably the most useful and adaptive one, as our mind is not initially evolved to deal with affairs unrelated to our own fitness status. Essentially, for irrelevant events that take place around us and things that happen far away from us, there is no need for us to respond to them and certainly no need for the concept of morality.

Moral System Based on Reason (MSR)

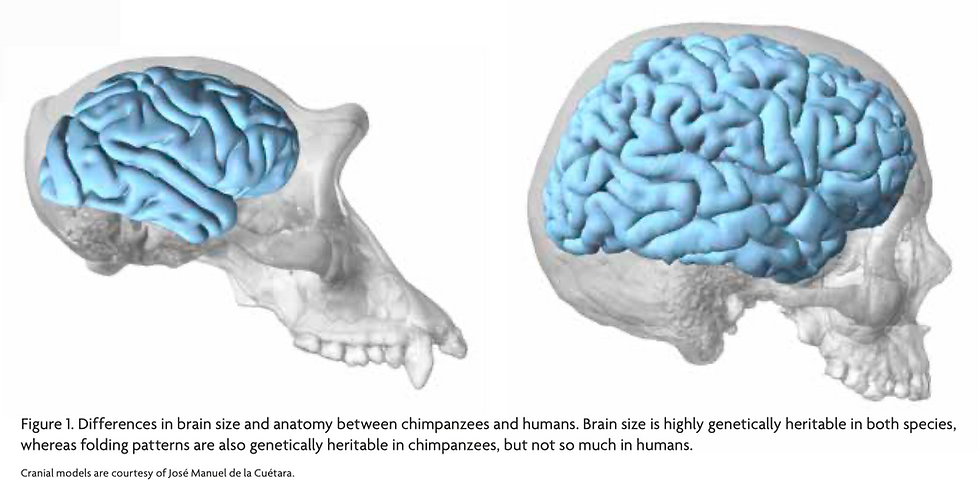

However, Homo sapiens is unique in a way that we have formed sociocultural systems, developed extremely large-scale cooperation, and brought cultural evolution onto the stage. Accompanied with the increased brain size and intelligence, the MSR was created, originally as the result of normalization and formalization of those moral concepts that we had derived from the MSE, but later on also added in religion, philosophy, and ethical concepts that were somewhat derived from reason in a more direct manner.

In the past, we were merely following our emotions to make moral judgments, but then we started to offer post hoc rationales for our decisions, externalizing and formalizing them to become prescriptive rules that we shall follow. However, the process of externalization is analogous to the process of translation, which means that it necessarily involves loss in information and accuracy. As we could see from the empirical studies discussed previously, our moral judgments are typically comprised of consideration of multiple factors and are really dependent on the specific scenarios. Therefore, for the derived explicit rules like “killing people is wrong,” “lying is wrong,” or “betraying your friend is wrong,” we can generally find counter-examples without difficulty since most of the rules we have formed are merely very simplified versions of our MSE and may sometimes be counter-intuitive.

On the next stage, religion and philosophy played important roles. While one of them made people believe in the stories they were told and follow the rules that were said to be given by God, the other was largely prescribing moral laws or axioms in a more rational and logical manner, involving reasoning and arguments. Nevertheless, there is actually no significant difference between those two, because both of them are products of combining the externalization of MSE and certain levels of rational thinking. Principally, the philosophical ideas like utilitarianism are nothing more than explicitly stated rules that fit partially with our MSE but involving some reasoning built upon the assumptions they have made. And it is probably the same story for moral concepts like “human rights” and “justice.” While the moral conclusions that “all humans are equal” and “people have basic human rights” are generalized by reason, our ability to empathize with each other and our capacity of theory of mind are probably serving as the underlying foundation for us to reach these conclusions.

Two Interacting Systems of Morality

Eventually, MSE and MSR were fully developed and were co-existing in our mind. They somewhat react to different stimuli, but there still exists a huge overlap between them. For example, for events that are close to us and related to us, we largely use MSE in making decisions, as they resemble the kind of scenarios that our ancestors have faced in the past. For those events that happen far away from us and originally irrelevant to our fitness, we largely use MSR in making those judgments, simply as automatic appraisals for the events. But it is important to realize that, for most of the time, these two systems are operating together and may either give the same conclusion or different conclusions. When the latter happens, moral dilemmas are formed, and people will struggle between the two conclusions. However, instead of only arising from the conflicts between MSE and MSR, conflicts could also arise just within MSR, as we have countless explicit rules and moral axioms that will inevitably conflict with each other sometimes.

More importantly, further complications are involved. After the externalization of MSE and the formation of MSR, our cognition changed and the antecedent events that our emotions reacted toward might have also shifted. In other words, the actual domain of our emotional responses becomes larger than the proper domain viewing from an adaptationist perspective. Although some moral concepts of MSR were initially out of the scope of MSE, MSE would gradually adopt those moral concepts and consider them to be morally related, therefore generating emotional responses toward those stimuli too. Finally, moral decisions become an intertwinement between MSE and MSR, acting in a manner similar to the dual-process model developed by Greene (2009) and the system 1 & system 2 model developed by Kahneman (2011). Generally speaking, MSE will be more likely to provide a fast judgment simply based on the level of emotional arousal we experience, in a manner similar to system 1. On the other hand, MSR will probably involve more attentional and computational efforts (e.g. calculating utility), potentially taking a longer time for the decision to be made, similar to system 2. This view has been widely supported by empirical research (Boccia et al., 2017; Conway & Gawronski, 2013; Cummins & Cummins, 2012; Guglielmo, 2015; Hutcherson, Montaser-Kouhsari, Woodward, & Rangel, 2015; Shenhav & Greene, 2014).

Conclusion

In this paper, we have discussed how MSR and MSE are constantly interacting with each other and resulting in the complex system of morality possessed by modern human beings. A potential evolutionario leading to their evolution has been introduced, and it is also in line with the well-substantiated dual-process model on the neural cognitive level. Then, what are some of the implications of this understanding towards human morality?

I think, taking a descriptive standpoint, we should probably abandon the view of human morality as something completely absolute and rational. The contingency involved in the evolutionary history and the potential mismatch between the proper and actual domain of primitive “morality” should be acknowledged. However, the critical distinction between the descriptive and prescriptive approaches needs to be again emphasized. As, even after we really acquire the complete descriptive knowledge about human morality, the debate on what “ought” to be the better choice will never end (e.g. effective altruism, see Bloom, 2016, 2017). Should we simply follow all of our natural instincts when making moral judgments? Or should we override them and make the more “ideal” choices? These are some crucial questions belonging to the field of philosophy for future discussion.

References

Baird, J. A., & Astington, J. W. (2004). The role of mental state understanding in the development of moral cognition and moral action. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2004(103), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.96

Berthoz, S., Grèzes, J., Armony, J. L., Passingham, R. E., & Dolan, R. J. (2006). Affective response to one’s own moral violations. NeuroImage, 31(2), 945–950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.039

Bloom, P. (2016). Against empathy: The case for rational compassion. London: Vintage.

Bloom, P. (2017). Empathy and its discontents. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(1), 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.11.004

Boccia, M., Dacquino, C., Piccardi, L., Cordellieri, P., Guariglia, C., Ferlazzo, F., … Giannini, A. M. (2017). Neural foundation of human moral reasoning: An ALE meta-analysis about the role of personal perspective. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 11, 278–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-016-9505-x

Conway, P., & Gawronski, B. (2013). Deontological and utilitarian inclinations in moral decision making: A process dissociation approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(2), 216–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031021

Cummins, D. D., & Cummins, R. C. (2012). Emotion and deliberative reasoning in moral judgment. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 328. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00328

Finger, E. C., Marsh, A. A., Kamel, N., Mitchell, D. G. V., & Blair, J. R. (2006). Caught in the act: The impact of audience on the neural response to morally and socially inappropriate behavior.NeuroImage, 33(1), 414–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.06.011

Gan, T., Lu, X., Li, W., Gui, D., Tang, H., Mai, X., … Luo, Y.-J. (2016). Temporal dynamics of the integration of intention and outcome in harmful and helpful moral judgment. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02022

Greene, J. D. (2001). An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science, 293(5537), 2105–2108. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1062872

Greene, J. D. (2009). Dual-process morality and the personal/impersonal distinction: A reply to McGuire, Langdon, Coltheart, and Mackenzie. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(3), 581–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.01.003

Greene, J. D., Cushman, F. A., Stewart, L. E., Lowenberg, K., Nystrom, L. E., & Cohen, J. D. (2009). Pushing moral buttons: The interaction between personal force and intention in moral judgment. Cognition, 111(3), 364–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2009.02.001

Guglielmo, S. (2015). Moral judgment as information processing: an integrative review. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1637. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01637

Hume, D. (1738). A treatise of human nature: Being an attempt to introduce the experimental method of reasoning into moral subjects. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hutcherson, C. A., Montaser-Kouhsari, L., Woodward, J., & Rangel, A. (2015). Emotional and utilitarian appraisals of moral dilemmas are encoded in separate areas and integrated in ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 35(36), 12593–12605. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3402-14.2015

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kant, I. (1998). Groundwork for the metaphysics of morals(M. Gregor, Ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Locke, J. (1975). An essay concerning human understanding(P. H. Nidditch, Ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Mill, J. S. (1998). Utilitarianism(R. Crisp, Ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nadelhoffer, T., & Feltz, A. (2008). The actor–observer bias and moral intuitions: Adding fuel to Sinnott-Armstrong’s fire. Neuroethics, 1(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-008-9015-7

Nobes, G., Panagiotaki, G., & Bartholomew, K. J. (2016). The influence of intention, outcome and question-wording on children’s and adults’ moral judgments. Cognition, 157, 190–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2016.08.019

Shenhav, A., & Greene, J. D. (2014). Integrative moral judgment: Dissociating the roles of the amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 34(13), 4741–4749. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3390-13.2014

Comments